Ten Years On: Prey

In terms of its hit-rate, Prey must be one of the worst franchises in the history of gaming. So far, it has produced precisely one game, which languished in development hell for over ten years before finally being released to warm, but not exactly glowing reviews. The open-world, free-running sequel looked tremendously exciting, but we never saw more of it than its initial (and still brilliant) announcement demo before the project was cancelled in 2014.This chequered past hasn’t stopped Bethesda from pressing onward with the IP, however. At this year’s E3 another entry in the series was unveiled, this time a reboot, also called Prey, set in the near-future and sporting a survival-horror emphasis. The ninety-second trailer was warmly received by the audience, a reaction which baffled me a little. The game looked decent, but even the more recent Quakecon trailer has offered very little to go on, while the series as a whole hasn’t done anything like enough to deserve such a rapturous reception.

Indeed, for some time now I’ve been trying to figure out why the Prey name is held in such high regard. Is it simply the mythos generated by the development woes of both the original and the sequel? Or is there more to it than that? Given that this summer also happens to be the tenth anniversary of the first game, I decided to return to Tommy’s adventure through the glistening corridors of the alien Dyson Sphere, to see if there’s any substance behind the peculiar reverence with which the IP is held.

And I think I’ve figured it out. What makes a new Prey such an alluring prospect is that the original is just close enough to greatness to make you wonder what it could have been if the development had been smoother, if it had launched when initially intended.

Before returning to Prey, I could recall exactly two things clearly about it. The first was the introduction, during which protagonist Tommy, his girlfriend Jen and his grandfather Anisi are abducted by a giant alien Dyson Sphere, its luminescent green tractor beams tearing apart the bar which Jen runs as Blue Oyster Cult’s 'Don’t Fear The Reaper', plays in the background. Like the rest of the game, it’s almost brilliant, a spectacular scene in which the drama is somewhat deflated by the one-dimensional characters and mediocre voice-acting.

But I mainly remember Prey for being the 'other' game with portals in it. Like Valve’s mini masterpiece, Prey features two-dimensional rips in space that the player can step through to be immediately transported to a different area of the environment. Again, it’s an excellent idea, but the impact is lessened by the fact that the Portals are entirely static, essentially doors that could only be seen from one side. Plus, at the time Valve had just started showing off Portal, which made Human Head’s game feel almost immediately outdated.

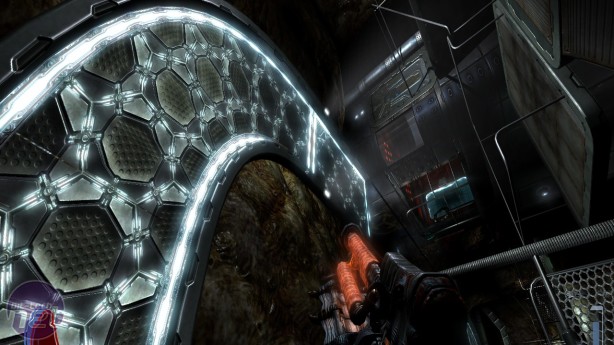

What I’d forgotten is that portals are just one of Prey’s delightful chocolate-box of space-manipulating ideas. Magnetic wall-walks allow Tommy to traverse walls and ceilings like a weaponised spider. Glowing blue panels flip the room’s gravity when shot. Tommy’s 'Spirit Walk' ability lets him leave his own body and slip through otherwise impassable barriers. There are even gigantic planetoids housed within the Dyson Sphere that sustain their own gravitational field.

Back in 2006, none of this made much of an impact upon me. But going back now, Prey’s approach to first-person movement and puzzling is surprisingly refreshing. Since the mid-2000s, most shooters have tended toward either cover-focussed action or sprawling open worlds. Prey genuinely thinks in three dimensions, and the developers have carefully considered how to bring every surface into the action. The way each room is built as both a combat arena and a spatial conundrum is highly enjoyable. Besides, shooting a gargling alien in the chops while stood upside-down is always going to be cool.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.