The 10 Best Cyberpunk Games

July 25, 2019 | 09:00

Companies: #bullfrog-productions #ion-storm #irrational-games #klei-entertainment #monolith-studios #square-enix #westwood-studios

It’s weird seeing Cyberpunk 2077 loom over the games industry like the glittering glass tower of an evil megacorp. I remember picking up an obscure little fantasy RPG in 2007 off the back of a review I read in PC Zone Magazine. 'It’s clunky as hell and more than a little sexist,' went the gist of the review, 'but there’s something interesting going on here as well.'

Who’d have thought that 12 years later that same developer would be making the most anticipated game in the world. And it got me thinking: 'Why?' Why is Cyberpunk that game? The one that’s right at the top of nearly everyone’s wishlist. No doubt the tech has something to do with it. It always does. But Cyberpunk started capturing imaginations long before CD Projekt showed any gameplay in action.

Then I started writing this list, and I realised just how few proper Cyberpunk games there actually are. Don’t get me wrong, loads of games have taken inspiration from that weird moment in the early 80s where Blade Runner and Neuromancer happened within a couple of years of one another. But comparatively fewer games deploy Cyberpunk in both aesthetic and theme – perhaps a couple of dozen at the very most – and there hasn’t been any that go all-in the way that Cyberpunk is doing.

That being said, there are a handful that will scratch that cyberpunk itch. Here are the best of them, in handy list format.

10. Transistor

Transistor is a love story wrapped in a corporate conspiracy wrapped in an isometric combat game set in a city themed around computers. You play as Red, an opera singer who lost her voice after being attacked by a mysterious force known as the Process. Red would have been killed outright, but at the last moment a man stepped in front of her, taking the blow of an almighty sword known as the Transistor. Now that man’s consciousness is trapped inside the sword, and he’s your only companion as the city of CloudBank starts to fall apart.

I was torn over Transistor when I first played it, as I made a point of mentioning in my review. But it is a pretty neat action game with a clever mechanic where you have to predict how enemies are going to move and lay out your own actions beforehand. Meanwhile its computerised cityscape makes for a fantastic backdrop to the game’s personal story. It isn’t the richest or most innovative cyberpunk game out there, but it is slick, stylish and doesn’t waste your time.

9. Blade Runner

Undoubtedly the most official Cyberpunk game on this list, Blade Runner is a 3D adventure game originally launched in 1997. It puts you in the trenchcoat of Ray McCoy a detective in the same vein as the film’s Rick Deckard with the same goal of hunting down a bunch of replicants gone rogue. Indeed, Blade Runner the game basically transplants the film’s story, using the same locations and basic plot points but with different characters.

Playing any adventure game made before the year 2000 is going to be an exercise in patience. But there are a couple of reasons why you might want to return to Blade Runner today (assuming you can find a copy). The first is that it’s the only game that lets you explore the original cyberpunk world, stroll the neon-soaked streets of Los Angeles 2019. The other is its intriguing real-time element. While Blade Runner is built on traditional adventure-game foundations, at the start of the game it randomly chooses which of its cast are replicants and which are humans, meaning you have to do some genuine detective work to figure out its mystery. Meanwhile, as you explore, those characters are doing their own things, resulting in timed events that it’s possible to miss, affecting the outcome of the game.

For its time Blade Runner was pretty darned innovative, and if it wasn’t for the fact it’s an adventure game (the popularity of which fell off a cliff around 1997) I think it would be remembered far more fondly than it is today.

8. Tron 2.0

I’m gonna level with you, I thought the original Tron was bobbins. The sequel is pretty rubbish too, albeit very pretty rubbish. Monolith’s inexplicable 2003 shooter, however, is really quite good, probably the best bit of Tron media going.

Tron 2.0 puts you in the role of Alan Bradley’s son, Jet, who ends up on a quest to rescue his kidnapped father. After being digitized, Jet ends up in conflict with an executive of FCon called J.D Thorne, who has become a virus spreading throughout the system.

At a glance, Tron 2.0 looks like a relatively straightforward FPS, but it actually has a heavy dose of RPG written into its code. Between its bouts of shooting are large portions of downtime where you can chat to friendly folk in the system, and there’s a (for the time) impressive upgrade system that lets you tailor your character in multiple different ways.

Tron 2.0 has also aged well for a 15-year-old FPS, with its simple, colourful aesthetic standing the test of time much better than a lot of shooters from around that era. It’s hardly the most thematically deep cyberpunk game, but it is one of the few that actually lets you explore a 3D representation of Cyberspace, and for that alone it deserves its place on this list.

7. Shadowrun Returns

Shadowrun is a mashup tabletop RPG setting where fantasy and cyberpunk collide. It’s the kind of game where you’ll chat to a grizzled orc bartender with a bionic arm before getting into a shootout with some gun-toting goblins. Shadowrun Returns interprets that world and its rulesets into a handy virtual format (let’s forget about the mediocre Microsoft-published shooter).

Gameplay wise, it blends X-Com style turn-based combat with extensive dialogue choices. The main draw here, however, is the story, a Gibson-esque detective yarn in which your character is contacted by a pre-recorded message of a close friend asking you to solve their murder. Cue a hunt for a serial killer through neon-soaked future Seattle, while various corporations and criminal organisations skulk in the shadows of your personal quest.

The original game is relatively short for an RPG, but it’s worth noting that Shadowrun has two expansions, one of which, Dragonfall, can be played standalone and is touted to be the best of the bunch.

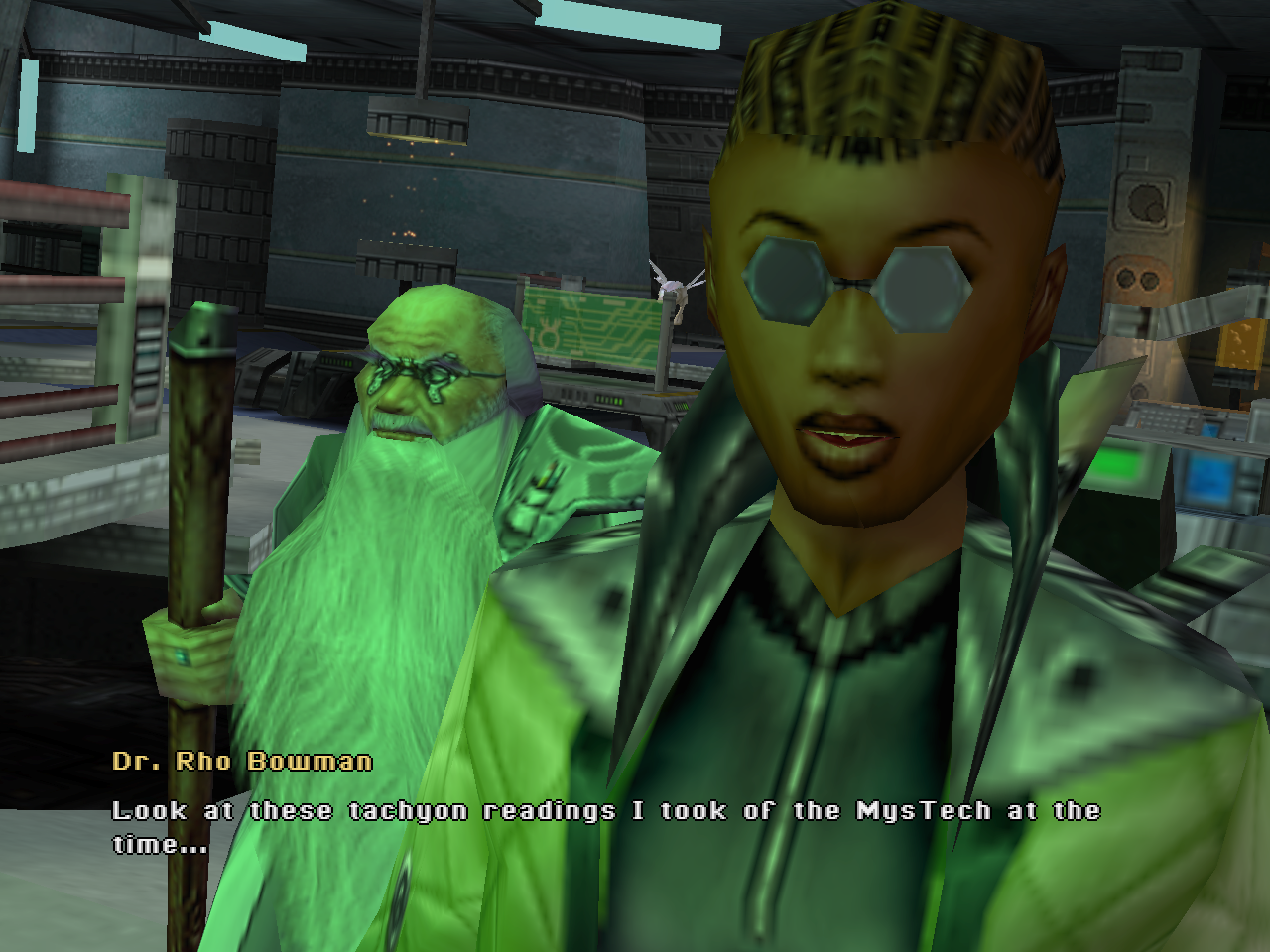

6. Anachronox

The other great cyberpunk game made by Ion Storm, Anachronox is a stupendously ambitious and equally hilarious RPG. You assume the role of Sly Boots, a private investigator living a slum life on the planet Anachronox, which is encased in a huge Dyson sphere. You start out on a simple investigation which quickly leads to a tremendous galaxy-spanning adventure.

In terms of play, Anachronox was heavily inspired by 1996’s Chrono Trigger, with similarly tactical turn-based combat. But like Shadowrun, the real draw here is the storytelling and particularly the loopy world-building. As a small example, you have a character in your party who is a planet. An actual planet.

Anachronox exists on the weirder edge of cyberpunk, teetering on the brink of hard sci-fi. It has a very different tone to most of the games on this list, less cynical and more tongue-in-cheek, with a lot of goofy humour. It’s also worth noting that, despite being 40-ish hours in length, the story isn’t actually finished and never was since Ion Storm Dallas closed within a month of the game’s launch. But even if the destination is ultimately disappointing, the journey itself is well worth experiencing.

5. Invisible, Inc

Most of the above games possess the aesthetic of cyberpunk, but Invisible, Inc is the first that really delves into the genre’s angsty punk soul. It sees you assume control of a team of rogue hacker-spies, infiltrating the glass fortresses of mega-corporations to steal data from within their firewalls. It features not just the cool cynicism typically associated with the genre, but that fist-clenching anger at the shocking disparity of wealth and power that cyberpunk futures so often portray.

Your goal in Invisible, Inc is to take a little of that power back, which you do through a whip-smart, turn-based stealth system that’s like X-Com wearing soft-soled shoes. It also features a clever hacking system wherein you utilise a benevolent AI to crack the complex security systems utilised by the corporations you steal from.

With fantastic visuals, an interesting story, and a tight runtime that lets you blast through a campaign within just a few hours, Invisible, Inc is well worth the attention of any cyberpunk fan.

4. System Shock 2

Transhumanism is one of the main themes of Cyberpunk, the notion that technology can be used to enhance the human body, and the question of how those enhancements might affect society and our perceptions of humanity. It’s a theme many games feature – any game with a skill system that lets you improve your character beyond the normal realms of human capability is transhumanist in some form – but few actively engage with.

System Shock 2 is different. In many ways the entire game is about transhumanism. Its story centres around a war between the AI SHODAN and a hive-minded creature known as The Many, which virally infects human bodies and mutates them to its own ends. Both creatures view themselves as superior, post-human beings, and both, ultimately, want you dead.

Your character is stuck in the middle of them, and to overcome these dual threats, you’re going to need abilities beyond the remit of your corporeal self. Fortunately, a friend somewhere on the derelict spaceship you’re trapped on provides you with Nanites, using which you can transform yourself into a military powerhouse, a hacking wizard, or an actual wizard, able to blow enemies to smithereens with devastating psionic powers.

But (and spoilers abound here) it soon transpires that all that upgrading you did was all thanks to SHODAN herself, who’s been stringing you along like a puppet for the game’s first half. She’s turned you into a weapon for her own ends, and even now you know it, you’re still going to do what she says, because otherwise The Many will absorb you into its mindless ranks.

There’s a whole other bunch of great things about System Shock 2 - its fantastic choice-based gameplay, its fantastic level design, its terrifying atmosphere - but the way it explores the thin line between humanity and monstrosity is one of its best and least talked about elements.

3. Deus Ex

In many ways, Deus Ex is the definitive cyberpunk game, which is curious because it was never really meant to be a cyberpunk game. Warren Spector’s vision for Deus Ex was an RPG in the style of System Shock or Ultima Underworld that took place in a believable version of our own world. The idea was not to make a game that was speculative, but realistic, one that looked back at the trajectory of the 90s and built a world based around that. Spector’s goal was to ask the question, 'What if all the conspiracy theories that have bubbled up over the last 10 years turned out to be true.'

That’s not to say that Deus Ex isn’t a cyberpunk game, simply that it wasn’t the primary goal. Weirdly, despite that, Deus Ex engages pretty actively with the major themes of the genre - the shift from government to corporate power, the effects of a world where humanity can upgrade itself, the prospective significance of AI. Indeed, Deus Ex essentially lifts the central plot of Neuromancer and adapts it for its Daedalus/Icarus subplot. Deus Ex may be partly a cyberpunk game by happy accident, but that doesn’t make its contribution to the genre any less significant.

2. Syndicate

Most cyberpunk games cast you as part of the downtrodden underclass; Syndicate puts you in the role of the boot. Bullfrog’s gleefully acerbic tactical strategy game sees you play a marketing director of a near-future corporation, tasked with maximising your company’s profits by essentially conquering the world.

In Syndicate, you take control of four cyborgs and embark on missions that range from assassinating members of rival corporations to brainwashing civilians to join your company. Each mission takes place in an open city that goes about its business as you trade gunfire with police and other corporate agents. As you progress you capture territories, which you can tax and spend the resulting income on weapon and equipment upgrades for your cyborgs.

The satire of Syndicate has all the subtlety of a pneumatic drill. But the significance of the game’s theme stems not so much from its critique of amoral corporations, but in showing players how amoral corporations come to exist and thrive. It hands you the power to be a ruthless, sadistic bastard and encourages you to enjoy being a ruthless, sadistic bastard. There are no repercussions for this, only ever higher tiers of reward. 'Oh, you killed a dozen civilians while trying to blow up that rival corp? That’s cool. Have a new gun.'

Syndicate shows us how easy it is to slide into moral reprehensibility by letting you experience the feeling yourself. It remains one of the smartest and most savagely political games ever made, and remains just as relevant today as it was 25 years ago.

1. Deus Ex: Human Revolution

From an RPG/immersive sim perspective, the original Deus Ex slightly has the edge over its more recent prequel. As Cyberpunk games, however, Human Revolution offers a far more nuanced and in-depth exploration of the genre’s themes. Whereas JC Denton is essentially an avatar for the player to inhabit, Adam Jensen is a man with a past of his own, and who infamously never asked for the augmentations he becomes equipped with early in the game.

Human Revolution is still a game about conspiracy theories but also far more speculative about the significance of an augmented society. The social hierarchy of Human Revolution is becoming increasingly split between those who can afford bodily augmentations and those who can’t. Meanwhile the price of Neuropozyne, a drug that prevents bodies from rejecting their augmentations, often forces people to take increasingly desperate measures to acquire it, giving rise to an underground trade in the drug that allows organised crime rings to flourish.

Perhaps Human Revolution’s most significant bit of world-building is its portrayal of corporate power. David Sarif, Jensen’s boss, is not the chin-stroking villain that Deus Ex’ Bob Page is, but an idealist whose company has rejuvenated Detroit and whose augmentations save Jensen’s life. Instead, Human Revolution shows us that corporate power often has a momentum of its own, a momentum that idealists like Sarif often lose control of. It shows us how easily that power can be misused and misdirected, and how even a small misdemeanour on the part of someone like Sarif can have massive consequences farther down the line.

For these reasons, Human Revolution edges its predecessor as a cyberpunk experience, and makes it currently the best Cyberpunk game going.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.