Fabled Lands: The MMO that Never Was

In 1995 I was on a boat, drifting carefree across a violet ocean on my way to an island, when a massive storm formed around me and began tossing my barge about like a bit of candlewax in a Jacuzzi. The crew were a motley bunch, mostly useless in the chaos and I wasn’t convinced the ship could take the strain. I wanted to believe otherwise, but my survival now rested only in the hands of Lady Luck.I'd been planning the trip for weeks and now everything depended on the role of a die, literally.

This isn’t a story from a computer game re-spun with a dash of new games journalism. If anything this is the opposite; old games journalism from back in the day when all the best stories were bound together with glue and stitching; gamebooks, basically. Specifically, it’s about the Fabled Lands series of gamebooks (called Quest in the US), which at one point almost managed to drop the ‘book’ suffix and go on to digital greatness as an MMO. Almost, but not quite.

As a long time fan of the series, I set out to find why the Fabled Lands series spent most of early 2000s buried in development hell, and what problems stopped authors Dave Morris and Jamie Thompson from turning their gamebook series into the UK’s answer to Final Fantasy. I made the decision to start at the very beginning, with the original gamebooks, mainly because I wanted to know about it personally – but it turned out that even the origins of the books were closely tied to the topic of computer games.

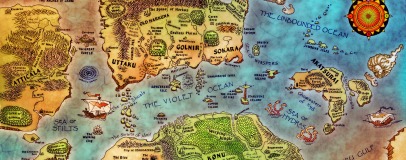

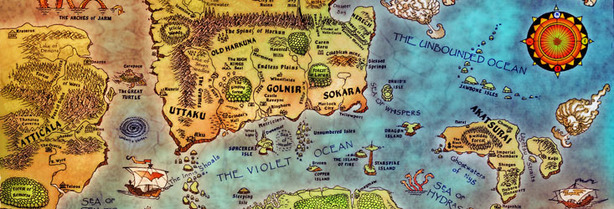

There were 12 Fabled Lands books originally planned, each A4-sized and illustrated, with a fold-out map

“Might & Magic would definitely be one inspiration,” says Dave Morris. “We liked the idea of being able to freely roam around a game world, not having to run on the rails of one single storyline like in most gamebooks…[In Fabled Lands] you can get involved in multiple quests, travelling back and forth between cities, trading, having random encounters. Everything you can do in a regular RPG really.”

Mechanically, a lot of ideas were borrowed from computer games too. Even the structure, with each book in the series representing a country you could visit, is similar to the process of buying expansion packs. The codeword system especially, where you’d tick off the codeword ‘Entropy’ if you’d fallen victim to the Hangman’s Curse, for example, was something that co-author Jamie Thompson said also came from computer games.

“We deliberately used codewords as if they were flags in computer games, like Might and Magic and stuff…We really wanted to make the world of your book feel like it changed according to the things you did. Some paragraphs became location paragraphs, like a city. You could go back there time after time, do inventory stuff but also it would change according to what you’d done before, and that’s where the codewords came in.”

The original plan for the Fabled Lands series was to create an entire world for players to explore, with the different countries and areas divided up over twelve books that players could travel between at will. The wind-swept steppes that made up Harkun’s most northern area was depicted in The Plains of Howling Darkness, while the ocean that Dweomer was situated in was part of a book called Over the Blood-Dark Sea. It was hugely ambitious and the pair had been trying for five years just to get the books off the ground before publisher Pan MacMillan stepped up.

“We’ve both been writing gamebooks so long that we have bug-checkers for the flowcharts running in our heads,” Dave says of the writing process. “The hard part was dreaming up so many different quests. We didn’t want it to be like those identikit games where you have to get the sword/book/kid and bring it to the castle/temple/city, over and over.”

Unfortunately, the Fabled Lands gamebooks ran into problems and only six of the proposed twelve games were ever released – the run ended with The Lords of the Rising Sun, which played off Japanese mythology in the same way that Howling Darkness zeroed in on nomadic culture. Price was a contentious issue considering the A4-paper size and fold-out colour maps; both writers feel that if the price had been raised from £5.99 to £7.99 then the series would have had chance to run it’s course.

“The first six books sold okay, but in our opinion the publishers weren’t charging enough,” says Dave. “They priced them to be competitive with Fighting Fantasy, but I think we were offering a lot more and production was expensive because of the size. In any case, the gamebook craze was dying out by then. We really needed to be working in computer games to do the things we wanted to do...”

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.