The Challenge

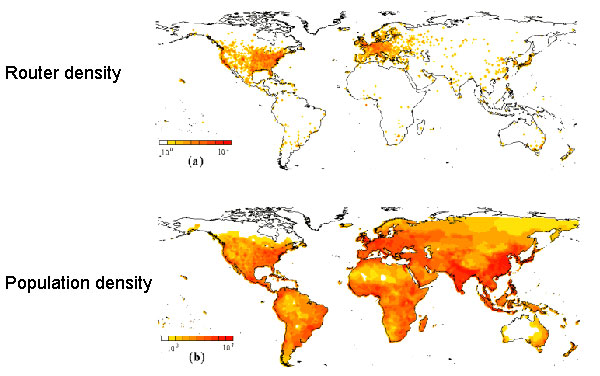

The proliferation of the personal computer is staggering. Within the space of two generations computers have gone from being giant room filling engines with less computing power than a Gameboy, to the modern state where a well equipped geek can have enough processing power in his pocket to calculate pi to millions of places over the course of his coffee break. But while it is easy to look at this spread of life-enriching technology as a great success, naturally this is not the story in the rest of the world. Computers, the web and all the goodies they bring remain the trappings of the wealthy, with even basic technology like telephones and radio yet to truly embed themselves in all parts of the developing world.This phenomenon, known as ‘the digital divide’, is becoming more pronounced. Whilst the percentage of those enjoying access to a PC for work, research and gaming in the developed world is increasing year on year, the less developed nations of the world are falling further behind.

A geographical representation of the digital divide, courtesy cybergeography.org

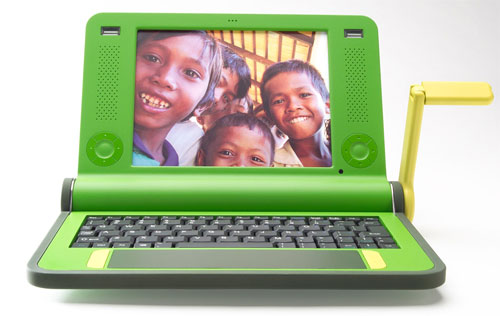

The most direct approach to tackling the digital divide has been a succession of plans to bring PCs to the children of less developed nations, partly to familiarise them with computers but also to assist them in their education in general.

What is needed for the developing world is a new kind of computer. Something durable, able to stand long journeys over poor or even non-existent road systems. A computer that can get a working supply of electricity without needing a stable power infrastructure. A system that can offer networking, web access and all the trappings of a modern western workstation using only free software. Most importantly it has to be a system that can be built from scratch for as little money as possible, with the magic number being touted as only $100 US, meaning that countries can afford to buy them.

Hardly the easiest design brief in the world, but then if building a PC for that sort of money was easy we’d all have one.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.