Researchers develop carbon nanotube computer

September 26, 2013 | 08:56

Companies: #research #researchers #stanford-university

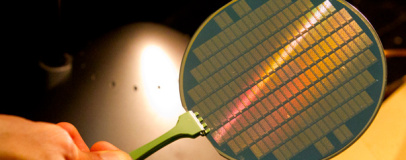

Researchers at Stanford University have built what is claimed to be the first fully-working computer based on a processor built from carbon nanotube transistors, in a move hoped to help string out Moore's Law for a few more decades.

Named for Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, Moore's Law is the observation that the complexity of computer circuits as measured by the number of transistors crammed onto a die roughly doubles every eighteen months. Although originally merely a historical observation, it has proved remarkably accurate in predicting - or, some would argue, defining - the growth of computing.

Now, however, Moore's Law is reaching its limits. Increasing the number of transistors in a given processor requires decreasing their size, and decreasing their size introduces a number of physics-related issues from heat generation to current leakage. As a result, some scientists believe that within the next few processor generations we will hit a hard size limit below which it will be impossible to manufacture a traditional processor.

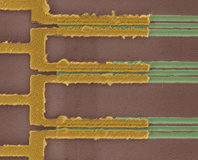

That's where non-traditional materials come in. A team at the Stanford Robust Systems Group claims to have developed the world's first working computer built using a microprocessor which uses carbon nanotube transistors in place of the more traditional type used in modern computing.

It's a move that others in the industry have been investigating - IBM, in particular, is a proponent of carbon nanotubes as one possible solution to the coming struggles to keep up with Moore's Law - but which has yet to be realised beyond small-scale experimental systems. 'People have been talking about a new era of carbon nanotube electronics moving beyond silicon,'[i] claimed Subhasish Mitra, lead professor on the project and an electrical engineer and computer scientist. '[i]But there have been few demonstrations of complete digital systems using this exciting technology. Here is the proof.'

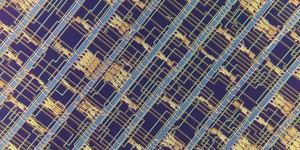

The computer, admittedly, is basic by modern standards: its processor is built on a process node of one micron - 1,000 nanometres, orders of magnitude larger than today's smallest 14nm parts - and features just 142 of the carbon nanotube transistors. That was enough, however, for the team to implement a small subset of the MIPS instruction set arcitecture and to produce what they claim is a Turing-complete, general-purpose programmable computer system.

The team has already shown the computer is capable of performing useful tasks, albeit slowly: using a customised multi-tasking operating system, the computer has performed counting and number-sorting operations - but the team claimed that the research is more than just the creation of a slow, expensive microcomputer. 'It's not just about the CNT computer,' explained Mitra. 'It's about a change in directions that shows you can build something real using nanotechnologies that move beyond silicon and its cousins.'

The team's work is published in the Nature journal this month.

Named for Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, Moore's Law is the observation that the complexity of computer circuits as measured by the number of transistors crammed onto a die roughly doubles every eighteen months. Although originally merely a historical observation, it has proved remarkably accurate in predicting - or, some would argue, defining - the growth of computing.

Now, however, Moore's Law is reaching its limits. Increasing the number of transistors in a given processor requires decreasing their size, and decreasing their size introduces a number of physics-related issues from heat generation to current leakage. As a result, some scientists believe that within the next few processor generations we will hit a hard size limit below which it will be impossible to manufacture a traditional processor.

That's where non-traditional materials come in. A team at the Stanford Robust Systems Group claims to have developed the world's first working computer built using a microprocessor which uses carbon nanotube transistors in place of the more traditional type used in modern computing.

It's a move that others in the industry have been investigating - IBM, in particular, is a proponent of carbon nanotubes as one possible solution to the coming struggles to keep up with Moore's Law - but which has yet to be realised beyond small-scale experimental systems. 'People have been talking about a new era of carbon nanotube electronics moving beyond silicon,'[i] claimed Subhasish Mitra, lead professor on the project and an electrical engineer and computer scientist. '[i]But there have been few demonstrations of complete digital systems using this exciting technology. Here is the proof.'

The computer, admittedly, is basic by modern standards: its processor is built on a process node of one micron - 1,000 nanometres, orders of magnitude larger than today's smallest 14nm parts - and features just 142 of the carbon nanotube transistors. That was enough, however, for the team to implement a small subset of the MIPS instruction set arcitecture and to produce what they claim is a Turing-complete, general-purpose programmable computer system.

The team has already shown the computer is capable of performing useful tasks, albeit slowly: using a customised multi-tasking operating system, the computer has performed counting and number-sorting operations - but the team claimed that the research is more than just the creation of a slow, expensive microcomputer. 'It's not just about the CNT computer,' explained Mitra. 'It's about a change in directions that shows you can build something real using nanotechnologies that move beyond silicon and its cousins.'

The team's work is published in the Nature journal this month.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.