If you travelled back to the year 2007 and told me that, in 2020, the most anticipated game on the planet was being developed by a Polish company best known for obscure fantasy RPG The Witcher, I would not have believed you. Granted, there’s a lot about the year 2020 that a time-traveller would find difficult to explain (President WHO?!?!), but that shouldn’t make CD Projekt’s journey from the Witcher to Cyberpunk any less remarkable.

As the date to Cyberpunk’s launch nears (although it recently got further away again), that journey has been increasingly on my mind. I found myself wanting to go back to the beginning, to explore in detail how CD Projekt went from scrappy underdog to one of the biggest developers in the world.

So that’s what I’m going to do. Over the next few months, I’m going to try to play all three Witcher games, chronicling my adventures in Geralt’s world as I go. I guess you could call this a let’s play. Only written in text, and with actual jokes and analysis rather than stupid noises and screaming.

Today, the original Witcher is known for being a somewhat sexist clunk-fest that escapes mediocrity via an interesting approach to moral choices. As someone who really enjoyed that original game, it’s a legacy that I’d love to revise. Unfortunately, the Witcher doesn’t do itself any favours by crashing to desktop twice before I’ve started the game – once when changing the graphics settings, and again when I try to Alt-tab to desktop.

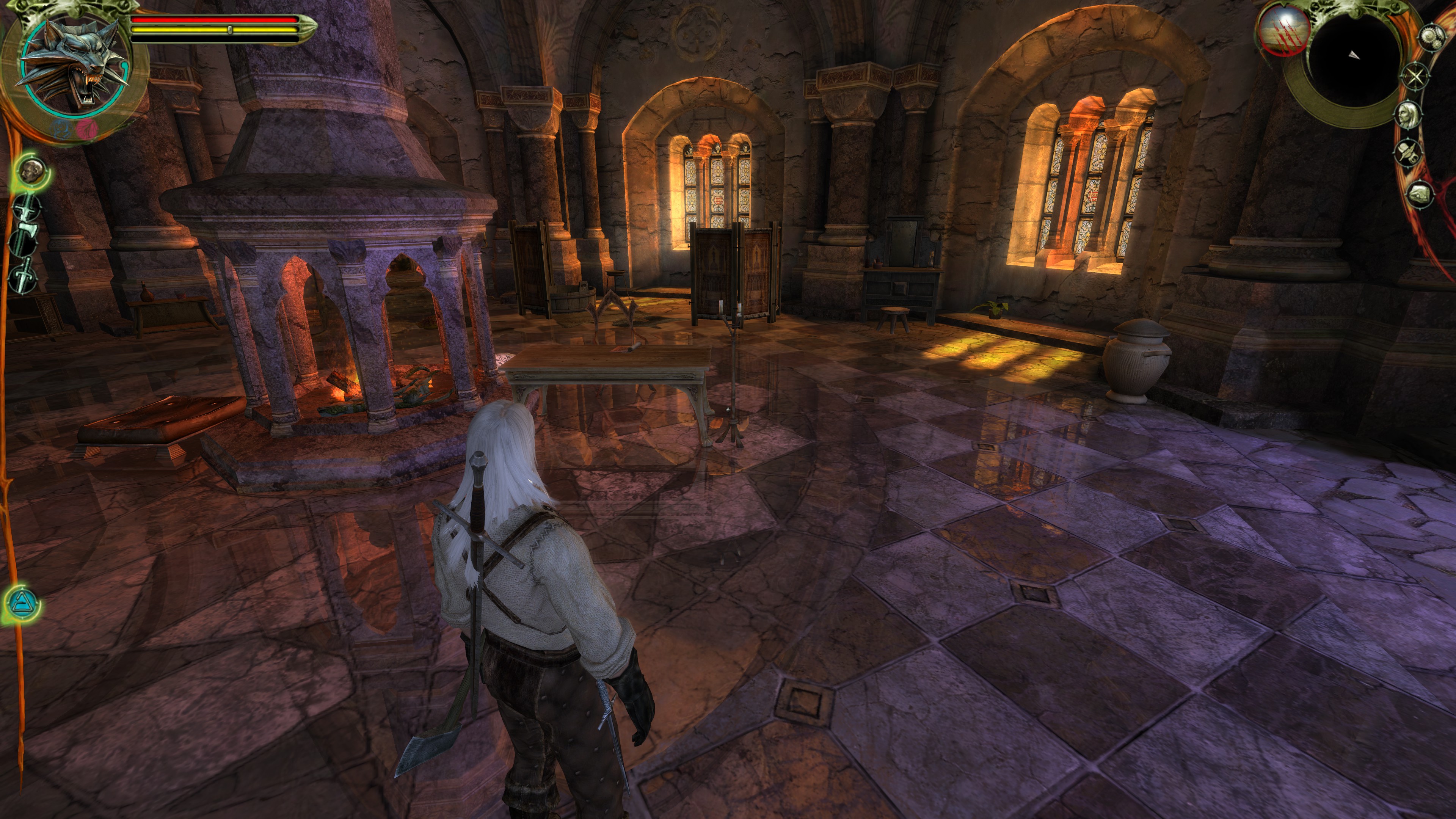

I’d also forgotten the original game lets players choose between two entirely separate control systems. You can play the whole game from an isometric perspective with point and click controls, or from a more modern OTS perspective with keyboard controls. Both have their advantages. The Witcher is more naturally a point-and-click game, especially when it comes to combat and navigation. But the OTS camera puts you physically inside the world, and for that reason it’s always the way I prefer to play.

The Witcher starts with a massive problem on its hands, namely the multiple novels that it takes place after, and the need to explain that world and all the characters in it to people who almost certainly haven’t read the books. It attempts to resolve this by giving Geralt amnesia, thereby aligning his worldly perspective with the player’s. The result is mixed, not least because Geralt dives straight into a whole bunch of relationships we’re not familiar with. The opening sequence alone introduces all the other Witchers, Triss Merigold and Geralt’s long-standing romantic entanglement with her, and your two main adversaries.

The introduction also has a far longer tail than I remember. Not only does the prologue at Kaer Morhen go on about twice as long as I expected it to, the game doesn’t actually stop teaching you how to play it until at least the end of Act 1. At one point I panicked because the game wouldn’t let me harvest plants to make potions. I thought I’d run into a bug, but it turns out herbalism is a talent you have to unlock by levelling up, something the game never explains.

It’s easy to poke at the Witcher for the things it gets wrong. But this first game also gets a lot right. Even in this first game, Geralt is a thoroughly enjoyable protagonist. CD Projekt’s vision of Geralt as a fantasy Philip Marlowe is evident from the off. You can hear the narrative designers trying to mimic the clipped, laconic tone of Chandler’s dialogue, that slang-heavy, confrontational tone which avoids characters making obvious responses to questions or accusations. Sometime the nuance is lost in translation, with characters respond in ways that seem to have no connection to the previous sentence. Fortunately, the vocal talents of Doug Cockle carry the strength of Geralt’s character through even his weakest lines.

Another of CD Projekt’s strengths that is obvious from the start is environment design. Act 1 takes place in the outskirts of the city of Vizima, an expanse of grassy fields and woodland dotted with villages and farmsteads. It’s probably the weakest part of any Witcher game, and yet it is nonetheless packed full of earthy character. The shifting routines of the NPCs through day and night lend a palpable sense of dynamism to the world, the peasant men and women gossiping as they wash clothes and chop wood. Children playing imaginative games on dirt tracks coated in mud and animal dung. The geese and chickens that scatter in a flurry of feathers as you run along the road, CD Projekt excel at representing the nuances of daily life. But there’s also a wildness to their landscapes that has become a hallmark of the Witcher games, a sense of eeriness and creeping dread of what lurks beyond the village boundaries.

This is what keeps you playing while CD Projekt spend Act 1 figuring things out, particularly how to blend the overarching plot with the fairy-tale threads that run through Sapkowski’s novels. In Act 1, Geralt is trying to track down a group known as Salamadra, responsible for stealing the Witchers’ unique mutation science. At the same time, he has to deal with a local monster problem in the form of a giant dog known as the Beast, who terrorises the peasants alongside its pack of spectral hounds called Barghests.

There’s division amongst the community as to who is responsible for the Beast’s appearance. Most of the village elders believe it’s the work of a local witch, but there are hints baked into the game world that this might not be the case. Unfortunately, these hints are a bit too implicit. For example, a wealthy local called Odo has problems with monstrous plants in his garden. After you help him deal with this issue, you discover Odo’s dog barking at a spot in the vegetable patch.

Coupled with the fact there’s a suit of armour in Odo’s house, a suit of armour he claims once belonged to his brother, there’s an implication that Odo murdered his sibling and buried him in his garden, which caused the monstrous plants to appear as well as contributing to the supernatural terror of the beast. Unfortunately, CD Projekt don’t make it clear that you’re supposed to be examining the environments like this, so this clue can easily be interpreted as a broken quest where you’re supposed to dig up the vegetable patch, but are never given an option to do so.

When the final confrontation between the villagers and Abigail comes around, you’re not necessarily furnished with all the facts because you didn’t know you were supposed to be looking for them in the first place. The Witcher constantly grapples with this issue throughout the first game, something that we’ll explore more when we enter Vizima proper next time.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.