Division has been Far Cry 2’s enduring legacy. You’ll struggle to find a game that has such polarised opinions on it. Some people maintain that it is the best game in the Far Cry series, while others despise it so much they’d like to go back in time and erase Clint Hocking’s memory if they could.

Personally, I agree that Far Cry 2 isn’t the best game in the series (that would be Far Cry 3). I do, however, think that it is the most important one. Not simply because of the many innovations it introduced which later entries would improve upon, but also because it’s a game that actually has something to say, rather than merely pretending it does.

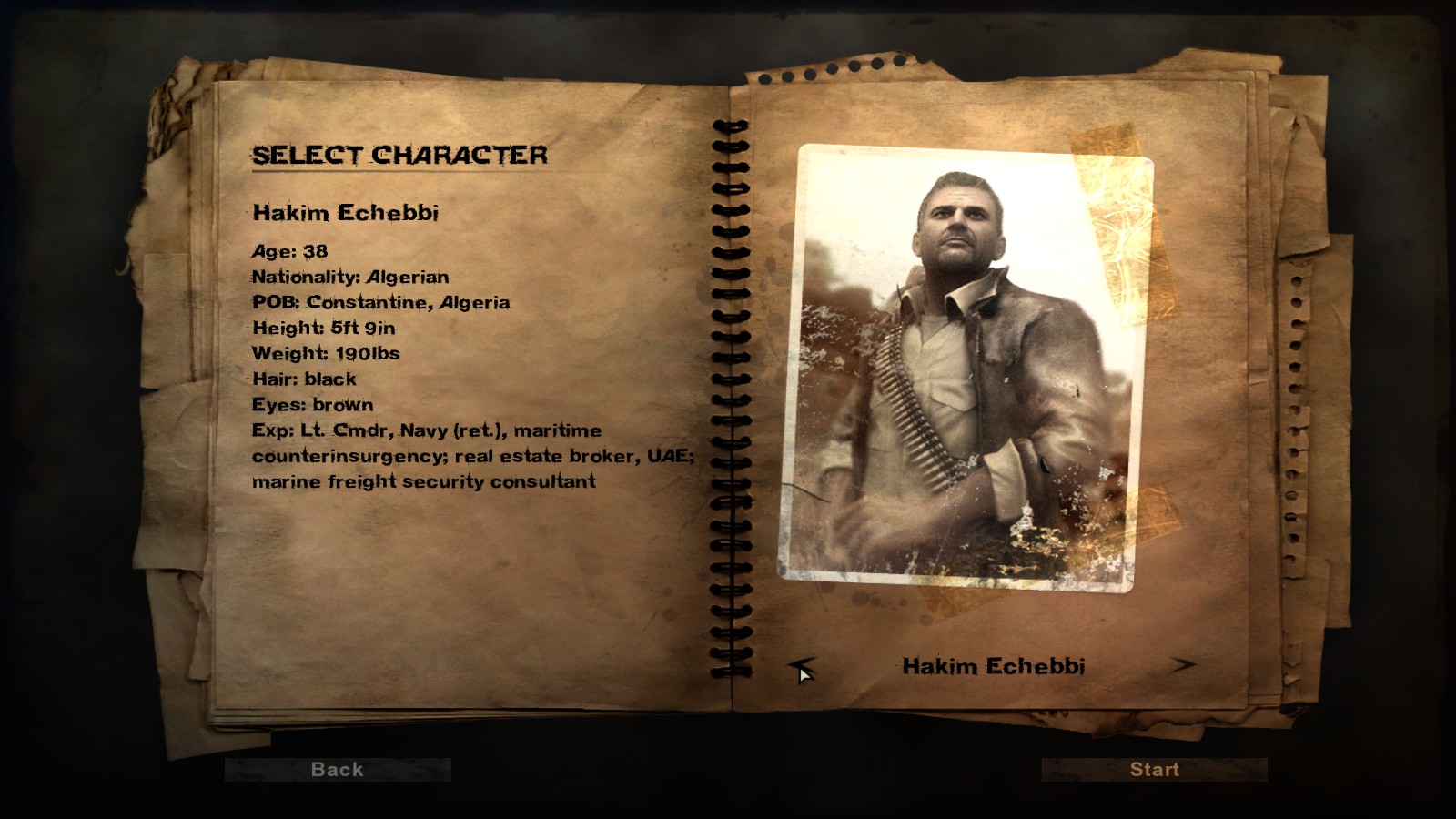

For those of you who don’t know or who have simply forgotten in the interceding decade, Far Cry 2 takes places in Africa, specifically a fictional central African state ravaged by civil war. It casts you as a mercenary who arrives in the country on a mission to track down and kill an arms dealer known as the Jackal, who has been fuelling the conflict by arming both sides.

There are loads of different elements of Far Cry 2 that I love, and I’ll talk about them in due course. But my overriding memory of experiencing the game for the first time is that the player-character would open doors with their hands. It was amazing! Before 2008, in most first-person games doors would magically open when interacted with, as if the player was controlling them telekinetically. Hence to see your Far Cry 2 character reaching out and interacting with objects like that was really powerful.

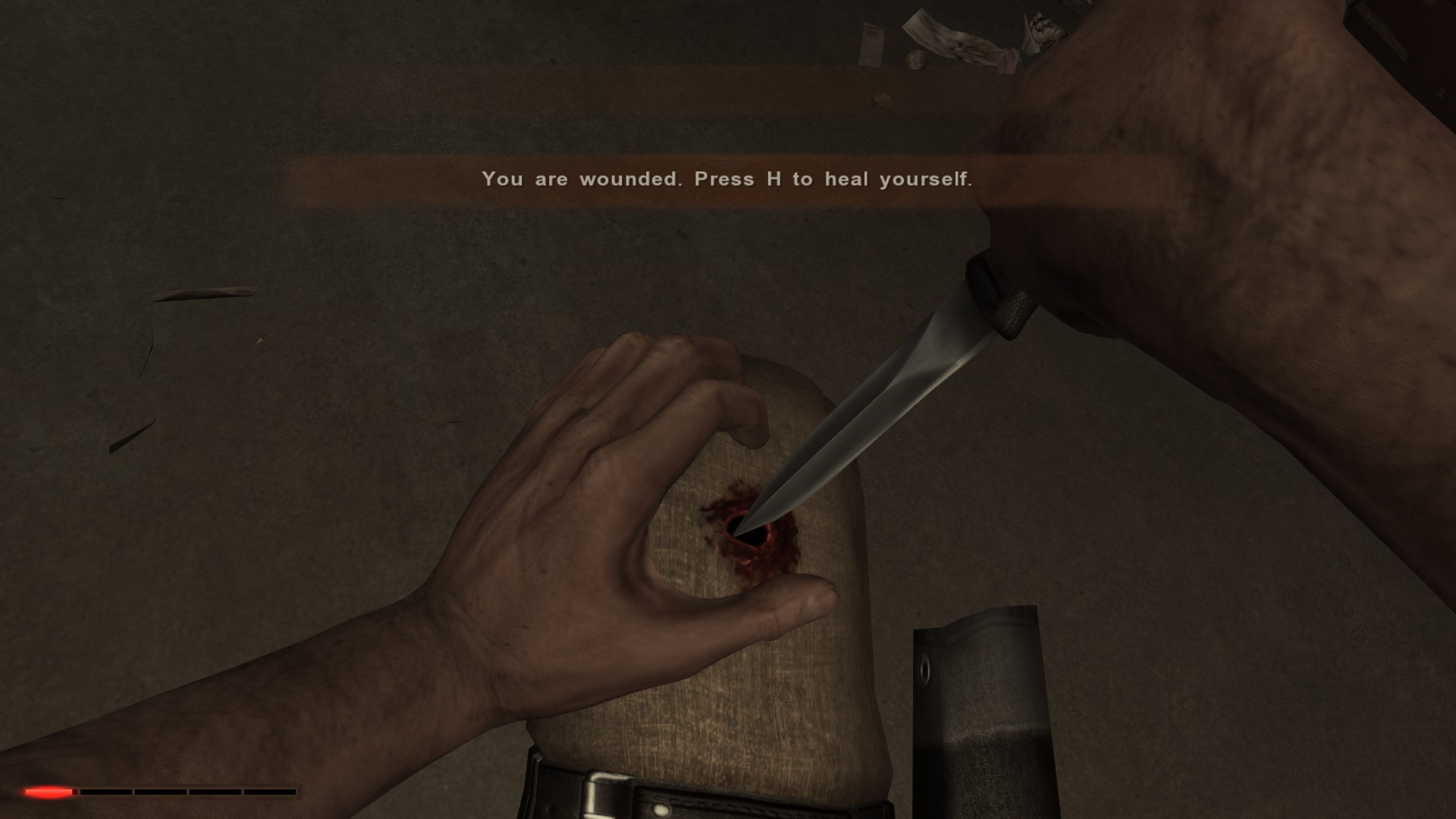

This little animation also clues into Far Cry 2’s overarching design philosophy, which was to produce an open world shooter that was as seamless and immersive as possible. When you get in a car, you physically climb into the seat. When you bring up the game map, it’s a physical map that you hold in your hand. When you start a fire, it spreads across the game’s arid grassland realistically. When you shoot an enemy, they’ll reel back and yell 'Ah fuck, I’ve been shot!'. When you get shot by an enemy, you have to physically pull the bullet out of your leg to heal.

It’s hard to stress just how incredible this stuff was at the time, and why I still find it annoying that some people complained about it. The fact that your character had Malaria and would have to take pills when symptoms appeared was one frequently aired grievance, even though all that’s required of you is to stock up on anti-malarials every few hours and take one when symptoms arose. I think many of the criticisms of Far Cry 2 are reasonable, but pointing out the inconvenience of being struck by malarial fever in the middle of a gunfight misses the point in at least two different ways.

All of these little details were designed to feed back into Far Cry 2’s emergent combat, to create scenarios that allowed players to plan their approach, but still had the capacity to surprise when the lead began to fly. One of my favourite tricks was to chuck some C4 into the back of my car, drive it straight into a checkpoint, leap out and then detonate the explosives. This would often result in me having to relocate a limb or put out a fire somewhere on my virtual body, but that didn’t stop it from being an effective way of clearing out checkpoints.

The biggest problem with Far Cry 2 is that many of its most interesting features have since been refined and improved by its sequels. The later games in the series have added more weapons and equipment, introduced much more visually appealing environments, and also sanded off some of Far Cry 2’s rougher edges. The constantly respawning checkpoints is the most obvious of these, but the sequels are also much better at smoothing out Far Cry’s feedback loops. Much like the first Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry 2’s biggest flaw is how its missions are overly formatted, offering little in the way of variety beyond what the player creates themselves.

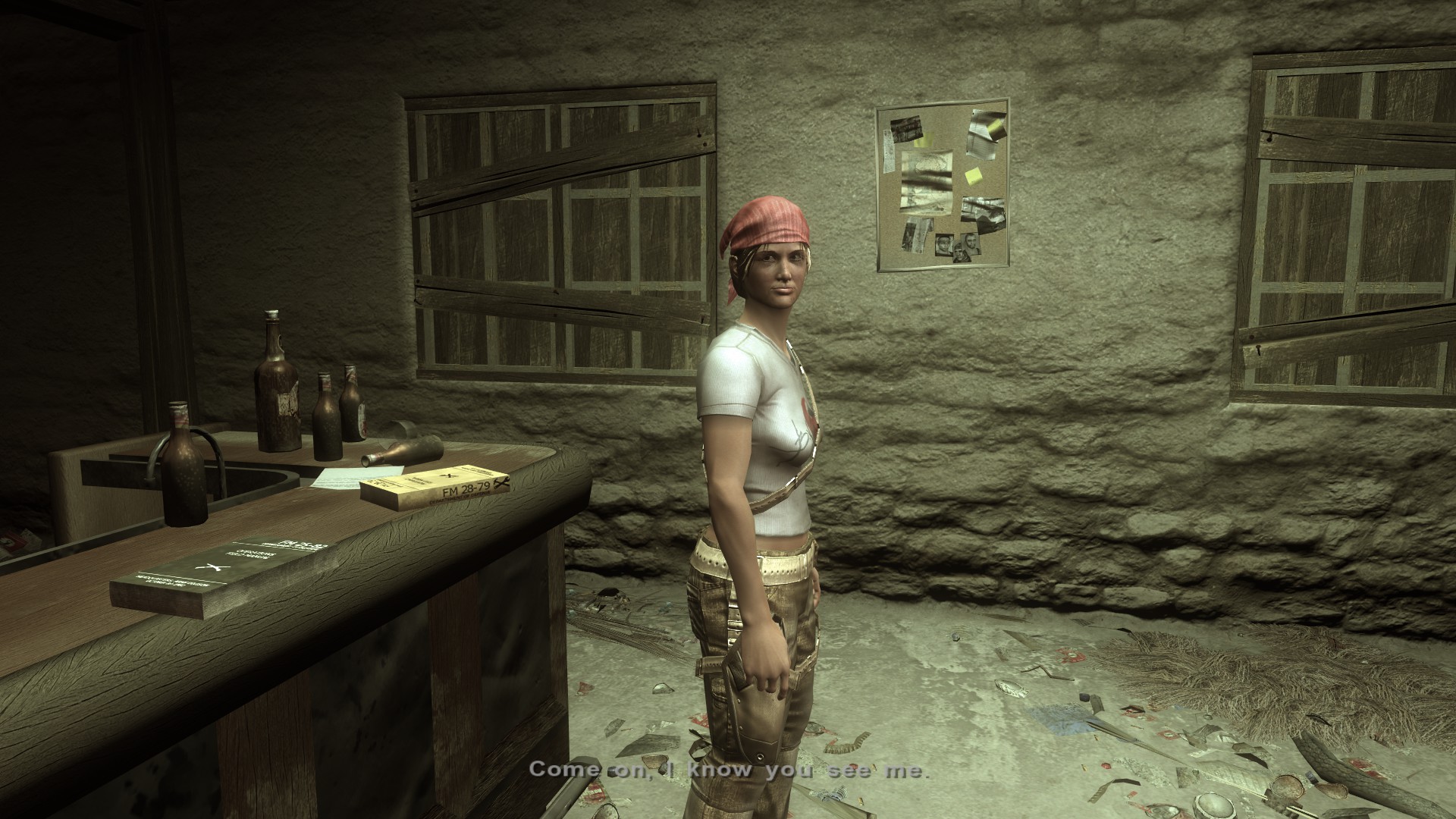

There are a couple of reasons that Far Cry 2 is worth returning to, however. The first is its buddy system. A major feature of the game involved rescuing other mercenaries from the country’s military factions, and these mercenaries could then be recruited to fight alongside you. If you died in a fight, they would essentially act as an extra life, picking you up, dusting you off, and then fighting alongside you until the coast was clear.

What’s more, they often did this at great personal risk, even to the point where they would could die permanently during a firefight. These mercenaries weren’t particularly interesting as characters (something that Far Cry 5 attempted to rectify with its own version of the buddy system), but seeing one killed during a battle having after having just pulled your arse from the fire was no less heartbreaking.

Far Cry 2 is a tough and uncompromising design, and it’s not surprising that as a consequence some people can’t stand it. But it’s entirely in-keeping with the game’s overall theme. Indeed, one of Far Cry 2’s most admirable traits is that it makes some effort to tackle the politics of its subject matter.

As I said, Far Cry 2 casts you as a foreign mercenary coming to Africa on a personal vendetta – to kill the Jackal. To do this, you exploit all the resources available to you in order to complete your mission. You happily fight for both of the game’s warring factions, playing them off one another purely for your own profit, while you also scour the land for briefcases containing diamonds, which you use to purchase guns and equipment.

Basically, it’s a parable for the West’s exploitation of Africa. You’re no hero, you’re just another invader scraping what cream they can from the top of the jug while the rest of the milk sours. It’s not a particularly subtle one, wearing its Heart of Darkness on its sleeve (oh, bravo! - ed.). Unlike its sequels, however, which boasted similarly bold themes and then shied away from any meaningful exploration, Far Cry 2 actually engages with its subject matter.

All the missions you embark on, the diamonds you earn, and the guns you buy bring about no resolution, only escalating chaos. The respawning checkpoints, annoying as they may be, also represent the pointless and cyclical nature of the conflict you’re embroiled in. Most notably, the end of the game sees your mercenary ways come back to haunt you, as it turns out that all the friendships you’ve established across the game are worth nothing compared to a case of diamonds and a ticket home.

I wish more people admired Far Cry 2 as I do, but perhaps division is a fitting legacy for a game about civil war that itself refuses to meet the player halfway. Yet while its aesthetic may be ugly, its dialogue weird, and its structure way too repetitive, Far Cry 2 has something that most mainstream games developed today sorely lack – a point.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.